“There’s no place, anywhere in the world, where the animals who live on the land get to own their own land.”

Lara Mostert is puzzled.

“How can this be?”

She says she’s tried to find an exception to the rule – but the only answer she can find is her own: a project that she and the company she works for (SAASA: the South African Animal Sanctuaries Alliance) have put together at Monkeyland, in The Crags near Plettenberg Bay.

Lara had what she later realised was an almost idyllic childhood – running free on the beaches and sand dunes of Melkbosstrand, outside Cape Town – before going on to study advertising at two different schools in the city. (“The first one didn’t believe in computers, so I had to go to a second one and do my computer studies at night.”)

“After I qualified, I decided I wanted to work in tourism, thinking that if I joined one of the big hotel chains, I’d get a chance to travel” – and while she didn’t land her dream job, she did complete a short course in tourism, and found herself working at the exclusive Inyati Game Lodge in the Sabi Sand Game Reserve, next to the Kruger National Park.

“That’s where I became friends with Tony (Blignaut - now her life partner), and in our free time we would go and sit under a tree together, where we always saw monkeys. I loved them, and I said, ‘Imagine if you had a game lodge where you only had monkeys.’

“Somehow, that idea grabbed him – he’d actually had the same idea ten years before – so whenever we took our breaks under the tree, he’d push me for my ideas about my ideal monkey sanctuary.

“But then he left the lodge, where he’d been a director, and went to live in the USA.”

Didn’t last long, though: Tony came back after only a few weeks.

“He phoned me at Inyati and said, ‘Do you still want to start Monkeyland?’ – and of course I said yes and dropped everything to go and join him.

“Together with his ex-partners, he put the finance together, and we opened Monkeyland just three years later, in April, 1998.”

It was a new concept in animal welfare: a rescue centre that offers the animals in its care the opportunity to live in a semi-wild state, in an environment that’s in many ways quite similar to their own, natural habitats. (It’s not always desirable to release previously captive animals into the wild – especially when they’re not indigenous to the host country.)

“Everyone said it would fail, though – even Nature Conservation predicted it – and we had to find investors who would carry the cost if it did fail.

“In those days, no one even knew what the word ‘primate’ meant, and I wanted to change that. But that needed activism – and I understood that for activism to work, it has to be fun.”

It was an insight she used powerfully when it came to marketing the business, too.

Lara’s often off-beat marketing gained her – and Monkeyland – quite a reputation: she handed out hundreds of bananas to po-faced delegates at South Africa’s premier tourism trade show – Indaba – and also hugged huge numbers of them, leaving each one unknowingly with a sticker on the back of their shirt or jacket: ‘I’d rather be at Monkeyland.’

But this also drew attention to the animals in SAASA’s care, attracted visitors in their thousands, helped stop animal touching experiences in sanctuaries and other facilities around the country – and, as we shall see – made Monkeyland a gold-award winner in the international responsible tourism arena.

DESTINY

“I believe in destiny, and that you should do something in life that’s meaningful,” said Lara.

“I don’t have children, so whatever I’ve made in life goes to – and will go to – the animals, because I was chosen to work with animals.

“I’d rather go without food than allow an animal to go without food.”

Lara, as you can tell, is passionate. It doesn’t stop with monkeys, though – although SAASA established a second Monkeyland in KwaZulu-Natal in April, 2019, she and Tony – she’ll insist that Tony does all the work – have also established Birds of Eden (opened in 2005), and now manage Jukani Wildlife Sanctuary, which provides a species-appropriate home for wild cats and other predators, many of which were rescued from circus performance, or from distressed zoos.

Both Birds of Eden and Jukani are also situated in The Crags.

Birds of Eden cares for previously caged birds in a 23,000 square metre, single-dome, free-flight aviary – the largest of its kind in the world – and also in a 900 square metre forested facility built especially for African grey parrots, which can’t be safely released into the general population.

“African greys live naturally in flocks – and not in the miserable single cages in which they are so often held as pets. South Africans are breeding far too many of them for the pet trade, and the species is becoming a problem for everyone who’s concerned for their welfare,” said Lara.

“We had more than 3,500 birds from more than 220 species in Birds of Eden before the pandemic started, and took in more than 700 others during lockdown. What else could we do? People lost the ability to look after their pets.

“And then we still had to feed everybody, even though we had no visitors coming through, and very little staff.

“During the early part of the pandemic, I spent most of my time in the kitchen cutting up fruit and vegetables for the birds and monkeys.”

#HandsOff

All of SAASA’s facilities enforce a no touch, #HandsOff policy, and have done since they were founded.

This was not the situation with many other facilities, though.

“I spent most of the early part of my career helping to convince the tourism industry in South Africa and around the world that ‘hands off’ is the only ethical approach, and gradually more and more people came to share our opinion.

“It’s very good to see that large companies like AirBnB and booking.com have now distanced themselves from petting wild animals, from circuses[1] that feature wild animals, and so on, and that our own Southern Africa Tourism Services Association (SATSA) has developed a toolkit with criteria for true sanctuaries or rehabilitation centres,” said Lara.

SATSA’s criteria for ethical animal interactions[2] include: no breeding or trading in wild animals; no performing animals; no touching or walking with wild animals (“no animals in tactile interactions”); animals should only be held in captivity if they are sick, injured, orphaned, rescued, donated and/or abandoned; the animals must either be given homes for life, used for in-situ repopulation through reintegration into the wild, or relocated via recognised conservation programmes; and the facilities in which the animals are held must comply with all relevant legislation, and must be transparent in their operations and marketing collateral.

WORLD RESPONSIBLE TOURISM AWARDS

SAASA’s – and Lara’s – ethical approach paid off for Monkeyland and its sister sanctuaries at the 2014 World Responsible Tourism Awards,[3] which were presented on World Responsible Tourism Day during London’s World Travel Market.

The Alliance was named Joint Overall Winners (with Brazil’s Campo and Parque Dos Sonhos[4]), and also joint Gold Award Winners (with UK-based World Animal Protection[5]) for the Best Animal Welfare Initiative.

For the overall gold award, the organisers said:

“The judges wanted to recognise two very different category winners. The [South African Animal] Sanctuary Alliance for demonstrating that animal attractions can liberate previously captive wildlife and, without petting or exploitation, be commercially successful. Parque dos Sonhos for demonstrating that truly inclusive tourism can enhance the adventure activity experiences for everyone and enable families and friends to share the experience. Both winners demonstrate that it is possible to address the rights agenda, to swim against the tide, and be commercially successful.” (responsible travel.com[6])

For the Best Animal Welfare Initiative Award[7], the judges (under chairperson Dr. Harold Goodwin[8], a Professor Emeritus and Responsible Tourism Director at the Institute of Place Management at Manchester Metropolitan University, and the responsible tourism programme adviser to World Travel Market) wrote that SAASA uses tourism,

“to help fund their conservation efforts, but they stress the importance of responsible tourism in this respect. One of its main achievements is to show visitors that petting and interacting with wild animals, as if they were domesticated, is irresponsible…. SAASA does not permit any activities that would place animals under stress and strives to educate tourists and tour operators on the reasons why not. Which include dangers to tourists, disease risks to both animals and tourists, and the fact that we are supporting unethical methods used to pacify wild animals enough so that they can be petted.

“...SAASA's exemplary practices and findings are now being used as benchmarks for future animal sanctuaries… other conservationists, students, media and animal-led organisations, [and] many international sanctuaries [now follow] in their footsteps.”

The judges also said that, “The South African Animal Sanctuary Alliance (SAASA) is like the supermodel of how sanctuaries should practise conservation and how they should present themselves on the world tourism stage.”[9]

SQUARE METRES FOR ANIMALS

“Getting petting and performance out of the way was an important place to start, but now it’s time to focus on a bigger issue: giving animals the right to own their own land, said Lara.”

She said that the rights of nature are well established in South Africa, as in many countries around the world. “There’s a whole branch of law that deals with the rights of nature or Earth Rights – which Wikipedia describes as “a legal and jurisprudential theory that describes inherent rights as associated with ecosystems and species, similar to the concept of fundamental human rights.”[10]

The general consensus seems to be that rights of nature law has as its foundation the publication of Christopher D. Stone’s 1972 article in the Southern California Law Review, ‘Should Trees Have Standing? Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects,’[11] which might be summed up in three quotes direct from the text:

(1) “The fact is, that each time there is a movement to confer rights onto some new "entity," [women, black people, animals] the proposal is bound to sound odd or frightening or laughable. This is partly because until the rightless thing receives its rights, we cannot see it as anything but a thing for the use of "us" – those who are holding rights at the time.”

(2) “...natural objects can communicate their wants (needs) to us, and in ways that are not terribly ambiguous. I am sure I can judge with more certainty and meaningfulness whether and when my lawn wants (needs) water, than the Attorney General can judge whether and when the United States wants (needs) to take an appeal from an adverse judgment by a lower court. The lawn tells me that it wants water by a certain dryness of the blades and soil – immediately obvious to the touch – the appearance of bald spots, yellowing, and a lack of springiness after being walked on; how does ‘the United States communicate to the Attorney General? For similar reasons, the guardian-attorney for a smog-endangered stand of pines could venture with more confidence that his client wants the smog stopped, than the directors of a corporation can assert that "the corporation" wants dividends declared.”

And:

(3) “As far as adjudicating the merits of a controversy is concerned, there is also a good case to be made for taking into account harm to the environment – in its own right. As indicated above, the traditional way of deciding whether to issue injunctions in law suits affecting the environment, at least where communal property is involved, has been to strike some sort of balance regarding the economic hardships on human beings… Why should the environment be of importance only indirectly, as lost profits to someone else? Why not throw into the balance the cost to the environment?”

Lara, though, would argue that rights and ownership[12] are different things.

“I have the right to own land, but unless I buy it, or unless it’s given to me, I don’t actually own it, and I can’t do what I like with it. And it’s the same for animals – or it could be, if we used the law to our advantage.”

Concerned for the future of the animals in their care (almost 6,000 at latest count), Tony and Lara began to wonder what would happen to them if either of them died, or if enough of the committed members of their board of directors died, too.

And what if the director’s heirs didn’t care for the future of SAASA’s animals the way they do?

“The crisis in tourism caused by the current pandemic has opened our eyes to the possibility that future generations of shareholders might not have the same passion for the animals that we do,” said Tony.

As Christopher Stone said: “it was clear [back in the medieval ages] how a king could bind himself – on his honor – by a treaty. But when the king died, what was it that was burdened with the obligations of, and claimed the rights under, the treaty his tangible hand had signed?’”

And so Lara and Tony decided on the only logical solution: Monkeyland had to be sold to the monkeys.

Not so easily done, though. Although the monkeys belonged technically to no one, the land belonged to the company’s original directors. And, despite more than fifty years of activism around the world, it seems that no country has yet enacted legislation that allows the creatures who have rights to a piece of land, to actually own that land.

“We had to make it possible for our existing non-profit to hold the land on behalf of the animals in what the lawyers call a ‘per proxima amici’ arrangement (‘by or through the next friend’) – and to fund that arrangement, we came up with our concept of selling squares metres on behalf of the primates,” said Lara.

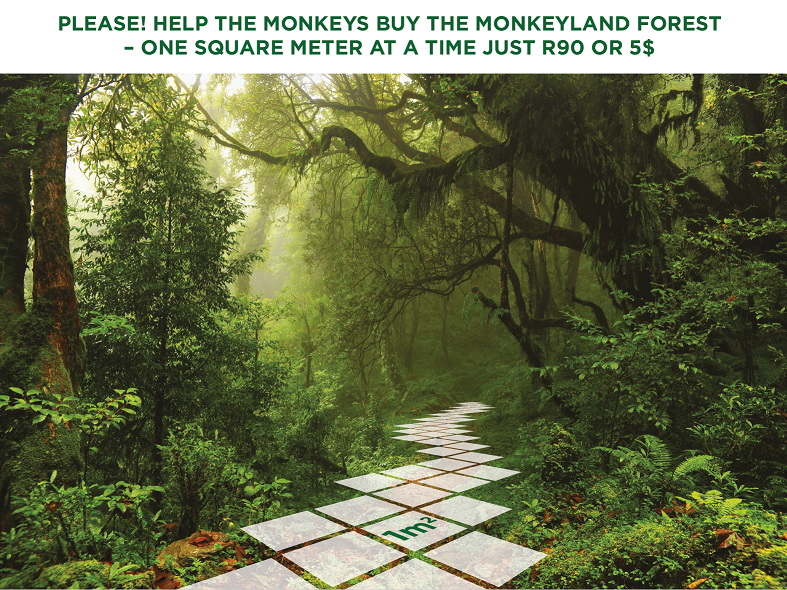

SAASA immediately set about negotiating the purchase of the land, and to finance the sale it set up a unique crowdfunding campaign that allows people and organisations to donate individual square metres at a cost of just US$5.00 (R90.00) per metre to the cause.

(Side note: Since SAASA is a registered Public Benefit Organisation, and since its ‘Buy a Square Meter’ campaign falls within its organisational objectives, such donations are tax deductible in terms of Section 18A of the Income Tax Act 58 of 1962.)

“With a total of 216,000 square metres available at Monkeyland – at $5 or R 90.00 per square metre (see map: https://www.tv/map/) – the campaign will raise more than the required amount, and the balance will go into an emergency fund to protect the animals’ food bill until such time as tourism returns to normal,” said Tony.

“We see giving the animals at Monkeyland rights to their own land in this way as a pilot project that will hopefully be rolled out to the other sanctuaries in the SAASA stable, and to many other facilities around the world, too,” said Tony.

As for Lara, she says she’ll only be satisfied when the deal is done.

“I don’t have many interests – I like to walk and I like to travel.” (Ironically, perhaps, she’s had more opportunities to travel for Monkeyland and SAASA than she could ever have imagined back when she was a young woman going into tourism for the first time. And she does like the occasional overseas holiday, too – usually on her own, or just with Tony. She prefers it that way.)

“But above all,” she said, “I love my animals – and seeing them safe is everything I need in life.”

ENDS

AUTHOR

Martin Hatchuel www.tourismcontent.co.za

14 May, 2022

MEDIA ENQUIRIES

Lara Mostert, lara@co.za +27(0)82 979 5683

NOTES TO EDITORS

Links

- Purchase a square metre of Monkeyland on behalf of it primates; https://www.tv/buy-a-square-meter-of-forest/

- SAASA - the South African Animal Sanctuaries Alliance: https://www.saasa.org.za

- Monkeyland, The Craggs: https://www.co.za

- Monkeyland, Ballito, Kwa-Zulu Natal: https://www.monkeylandkzn.co.za

- Birds of Eden: https://www.birdsofeden.co.za

- Jukani Wildlife Sanctuary: https://www.jukani.co.za

NPO registration

- The South African Animal Sanctuary Alliance (SAASA) NPO number: 008-464

Sanctuaries in SAASA’s stable

- Monkeyland, The Crags, Plettenberg Bay

This is an area of tall yellowwoods, stinkwoods, and white pear trees, where the resident primates (including Capuchin monkeys, ring-tailed and black-and-white ruffed lemurs, gibbons, howler monkeys and more) are free to form their own family groups, and to socialise amongst themselves as they normally would – without interference from the guests. (“There are no fences between our visitors and the monkeys at Monkeyland, but we’re strict about enforcing our non-negotiable, ‘no petting’ rule,” said SAASA CEO, Tony Blignaut.)

Visitors are treated to guided walking tours – ‘monkey safaris’ – which depart every half hour from the centre’s reception complex, which is open every day of the year.

Attractions at Monkeyland include a one hundred and twenty eight-metre suspension bridge that spans a deep gorge in the forest. This allows visitors to view many of the monkeys as they go about their daily lives high up in the canopy of the trees – and provides some of the best photo opportunities in a sanctuary that’s become known for spectacular photo opportunities.

A second Monkeyland sanctuary was established in Ballito, in Kwa-Zulu Natal, in 2019.

- Monkeyland, The Crags, Plettenberg Bay: https://www.co.za

- Monkeyland, Ballito, Kwa-Zulu Natal: https://www.monkeylandkzn.co.za

- Birds of Eden

“In the same way you can’t release non-indigenous animals into the wild, you can’t just release captive birds and expect them to fend for themselves – both because of the threat to the individual birds themselves, and because of the danger that they could become invasive, and so threaten the country’s natural biodiversity, as has happened with species like the Indian myna and the house crow,” said Tony.

His solution was to create the world’s largest free-flight dome aviary by spanning a wire mesh structure over 23,000 square metres of a second, partly-forested gorge close to

Birds of Eden is now home to nearly 4,500 birds belonging to more than two hundred and twenty different species, and, since many of these individuals were previously held in tiny cages in private homes, most of them had to go through a rehabilitation process to learn to socialise with other birds before release into the dome.

Now, with 1.2 km of winding wooden boardwalks that meander through the trees and past rushing waterfalls and tranquil ponds, Birds of Eden is both a comfortable home for its residents, and a fun-filled destination for guests. Tours here are self-guided, although guides are available at no extra cost.

- Birds of Eden: https://www.birdsofeden.co.za

- Jukani Wildlife Sanctuary

Jukani bills itself as being a space ‘where rescued big cats feel at home.’ As with SAASA’s other sanctuaries, it was created to provide rescued animals with large natural habitats designed around the individual species’ needs, and in which they can live out their lives in peace and comfort.

This sanctuary focuses on apex predators – lions, tigers, leopards, pumas, caracals, jaguars, etc. – that required rehoming (usually from facilities that find themselves unable to care for them: distressed zoos, circuses, etc.).

Visitors are treated to 80-minute guided tours, and also to sightings of animals like raccoons, a honey badger, African polecat, and spotted hyena – as well as small herds of springbok and zebra.

“Like all our sanctuaries, Jukani is suitable for all ages and fitness levels, and it’s wheelchair-friendly, too” said Tony.

Facilities include a gift shop – profits support the welfare of Jukani’s inhabitants – while restaurant facilities are available at Monkeyland and Birds of Eden, just a few kilometres to the east.

- Jukani: https://www.jukani.co.za

// General Notes

ADDITIONAL NOTES: SHOULD TREES HAVE STANDING

Excerpts from Christopher Stone’s ‘Should Trees Have Standing?’[13]

Page 455: “The fact is, that each time there is a movement to confer rights onto some new "entity," the proposal is bound to sound odd or frightening or laughable. This is partly because until the rightless thing receives its rights, we cannot see it as anything but a thing for the use of "us" – those who are holding rights at the time.”

++++

Page 463: “Even where special measures have been taken to conserve them (living things), as by seasons on game and limits on timber cutting, the dominant motive has been to conserve them for us – for the greatest good of the greatest number of human beings. Conservationists, so far as I am aware, are generally reluctant to maintain otherwise. As the name implies, they want to conserve and guarantee our consumption and our enjoyment of these other living things. In their own right, natural objects have counted for little, in law as in popular movements.”

++++

Page 464: “It is not inevitable, nor is it wise, that natural objects should have no rights to seek redress in their own behalf. It is no answer to say that streams and forests cannot have standing because streams and forests cannot speak. Corporations cannot speak either; nor can states, estates, infants, incompetents, municipalities or universities. Lawyers speak for them, as they customarily do for the ordinary citizen with legal problems. One ought, I think, to handle the legal problems of natural objects as one does the problems of legal incompetents – human beings who have become vegetable. If a human being shows signs of becoming senile and has affairs that he is de jure incompetent to manage, those concerned with his well being make such a showing to the court, and someone is designated by the court with the authority to manage the incompetent's affairs. The guardian (or "conservator" or "committee" – the terminology varies) then represents the incompetent in his legal affairs. Courts make similar appointments when a corporation has become "incompetent" – they appoint a trustee in bankruptcy or reorganization to oversee its affairs and speak for it in court when that becomes necessary.

“On a parity of reasoning, we should have a system in which, when a friend of a natural object perceives it to be endangered, he can apply to a court for the creation of a guardianship.”

++++

Page 471: “The guardianship approach, however, is apt to raise two objections, neither of which seems to me to have much force. The first is that a committee or guardian could not judge the needs of the river or forest in its charge; indeed, the very concept of "needs," it might be said, could be used here only in the most metaphorical way. The second objection is that such a system would not be much different from what we now have: is not the Department of Interior already such a guardian for public lands, and do not most states have legislation empowering their attorneys general to seek relief-in a sort of parens patriae way- for such injuries as a guardian might concern himself with?

“As for the first objection, natural objects can communicate their wants (needs) to us, and in ways that are not terribly ambiguous. I am sure I can judge with more certainty and meaningfulness whether and when my lawn wants (needs) water, than the Attorney General can judge whether and when the United States wants (needs) to take an appeal from an adverse judgment by a lower court. The lawn tells me that it wants water by a certain dryness of the blades and soil – immediately obvious to the touch – the appearance of bald spots, yellowing, and a lack of springiness after being walked on; how does "the United States" communicate to the Attorney General? For similar reasons, the guardian-attorney for a smog-endangered stand of pines could venture with more confidence that his client wants the smog stopped, than the directors of a corporation can assert that "the corporation" wants dividends declared.”

++++

Page 472: “Besides, what a person wants, fully to secure his rights, is the ability to retain independent counsel even when, and perhaps especially when, the government is acting "for him" in a beneficent way. I have no reason to doubt, for example, that the Social Security System is being managed "for me"; but I would not want to abdicate my right to challenge its actions as they affect me, should the need arise.76 I would not ask more trust of national forests, vis-a-vis the Department of Interior. The same considerations apply in the instance of local agencies, such as regional water pollution boards, whose members' expertise in pollution matters is often all too credible.”

++++

Pages 473-4 “As far as adjudicating the merits of a controversy is concerned, there is also a good case to be made for taking into account harm to the environment – in its own right. As indicated above, the traditional way of deciding whether to issue injunctions in law suits affecting the environment, at least where communal property is involved, has been to strike some sort of balance regarding the economic hardships on human beings… Why should the environment be of importance only indirectly, as lost profits to someone else? Why not throw into the balance the cost to the environment?”

++++

Pages 475-6: “I propose going beyond gathering up the loose ends of what most people would presently recognize as economically valid damages. The guardian would urge before the court injuries not presently cognizable-the death of eagles and inedible crabs, the suf- fering of sea lions, the loss from the face of the earth of species of commercially valueless birds, the disappearance of a wilderness area. One might, of course, speak of the damages involved as "damages" to us humans, and indeed, the widespread growth of environmental groups shows that human beings do feel these losses. But they are not, at present, economically measurable losses: how can they have a monetary value for the guardian to prove in court?

“The answer for me is simple. Wherever it carves out "property" rights, the legal system is engaged in the process of creating monetary worth. One's literary works would have minimal monetary value if anyone could copy them at will. Their economic value to the author is a product of the law of copyright; the person who copies a copyrighted book has to bear a cost to the copyright-holder because the law says he must.

“I am proposing we do the same with eagles and wilderness areas as we do with copyrighted works, patented inventions, and privacy: make the violation of rights in them to be a cost by declaring the "pirating" of them to be the invasion of a property interest. If we do so, the net social costs the polluter would be confronted with would include not only the extended homocentric costs of his pollution… but also costs to the environment per se.”

++++

Page 498: “A few years ago the pollution of streams was thought of only as a problem of smelly, unsightly, unpotable water i.e., to us. Now we are beginning to discover that pollution is a process that destroys wondrously subtle balances of life within the water, and as between the water and its banks. This heightened awareness enlarges our sense of the dangers to us. But it also enlarges our empathy. We are not only developing the scientific capacity, but we are cultivating the personal capacities within us to recognize more and more the ways in which nature – like the woman, the Black, the Indian and the Alien – is like us (and we will also become more able realistically to define, confront, live with and admire the ways in which we are all different).”

++++

D. Rudhyar, 'Directives for new life’ 21·23 (1971) quoted in Stone, C., page 498: “Ever since the first Geophysical Year, international scientific studies have shown irrefutably that the Earth as a whole is an organized system of most closely interrelated and indeed inter- dependent activities. It is, in the broadest sense of the term, an "organism." The so-called life-kingdoms and the many vegetable and animal species are dependent upon each other for survival in a balanced condition of planet-wide existence; and they depend on their environment,. conditioned by oceanic and atmospheric cur- rents, and even more by the protective action of the ionosphere and many other factors which have definite rhythms of operation. Mankind is part of this organic planetary whole; and there can be no truly new global society, and perhaps in the present state of affairs no society at all, as long as man will not recognize, accept and enjoy the fact that mankind has a definite function to perform within this planetary organism of which it is an active part.”

[1] Getaway, 21 October 2019: ‘Travel sites stop selling tickets to captive animal performances’ https://www.getaway.co.za/travel-news/travel-sites-stop-selling-tickets-to-captive-animal-performances/

[2] SATSA: ‘Evaluating Captive Wildlife Attractions & Activities. A tool to help you make good choices’ https://www.satsa.com/wp-content/uploads/SATSA_HumanAnimalInteractions_Tool6.pdf

[3] WTM – World Responsible Tourism Awards: https://hub.wtm.com/press/world-responsible-tourism-awards/

[4] Campo and Parque Dos Sonhos: http://www.campodossonhos.com.br/

[5] World Animal Protection: https://www.worldanimalprotection.org

[6] responsibletravel.com: ‘2014 World Responsible Tourism Awards Winners’ https://www.responsibletravel.com/holidays/responsible-tourism/travel-guide/2014-awards-winners

[7] responsibletravel.com: ‘Best Animal Welfare Initiative’ https://www.responsibletravel.com/holidays/responsible-tourism/travel-guide/wildlife-and-habitats-awards-category

[8] Dr. Harold Godwin: https://haroldgoodwin.info

[9] WTM, Animal Welfare Initiative Award, 2014 winers https://www.responsibletravel.com/holidays/responsible-tourism/travel-guide/wildlife-and-habitats-awards-category

[10] Wikipedia, ‘Rights of Nature’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rights_of_nature

[11] Stone, Christopher D. ‘Should Trees Have Standing? – Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects.’ Southern California Law Review 45 (1972): 450-501 https://iseethics.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/stone-christopher-d-should-trees-have-standing.pdf

[12] wikidiff.com: ‘Right vs Ownership - What's the difference?’ https://wikidiff.com/ownership/right: “As nouns the difference between right and ownership is that right is that which complies with justice, law or reason while ownership is the state of having complete legal control of the status of something.”

[13] Stone, Christopher D. “Should Trees Have Standing? – Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects.” Southern California Law Review 45 (1972): 450-501 https://iseethics.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/stone-christopher-d-should-trees-have-standing.pdf